A narrative experience about the power of regret.

Emotional, story-driven games like South of the Circle (SotC) are not, for better or worse, everyone’s cup of tea. Originally released in 2021 for Apple Arcade, it was developed by State of Play, published by 11 Bit Studios, and is a compelling story of ambition and love set around the Cold War.

I played SotC on the Nintendo Switch to write this review and was pleasantly surprised by what I found, but not in the way you might expect.

As SotC was originally a mobile game, do not expect high-end graphics. Don’t get me wrong, many mobile devices are capable of high-resolution textures and visuals that other reviewers would no doubt refer to as ‘eye-popping’, but that isn’t what State of Play went for here.

SotC uses an almost comic-book style shader to bring its 3D models to life, as well as motion capture performances and a striking use of colour. While the game may look like a comic book, as the embedded screenshots and videos hopefully demonstrate, the facial animations, simple as they are, are wonderfully translated from the actor’s performance and convey a depth of feeling that many AAA titles strive for, and fail to achieve, with photo-realistic graphics.

I’ve seen comic panels that look worse.

Where the graphics are relatively minimalistic, relying largely on bright splashes of colour with minimal shading, the soundtrack is phenomenal. A swelling composition that matches the story beat for beat, the music is definitely used here as part of the game and the storytelling, rather than being used as a background element designed to enhance the experience.

As SotC is primarily a narrative-experience, the soundtrack shifts to accommodate each narrative beat, often in time with dramatic camera pans, and ensures that the emotional resonance the developers intended is effortlessly created.

While I won’t find myself humming any of the music on offer here, SotC would not hit as hard as it does without its score.

Good music, good visuals, and good vibes

The script is powerfully delivered by an all-star cast of actors from television and movies.

Score, of course, isn’t the only form of audio in most video games and the voice acting here is superb. The voice cast contains some of the finest actors around, some of whom have previous voice acting experience, and they consistently knocked it out of the park with their delivery. Games like this are made or broken by two things: the writing and the voice cast.

I’ll discuss the writing below, but the voice cast deserve all the praise I can heap upon them for clearly conveying the frustration, confusion, joy, curiosity, and despair of their character. Not once did I think that a line failed to land correctly and a part of me wishes there were more of the game to experience so I could continue to enjoy their performances.

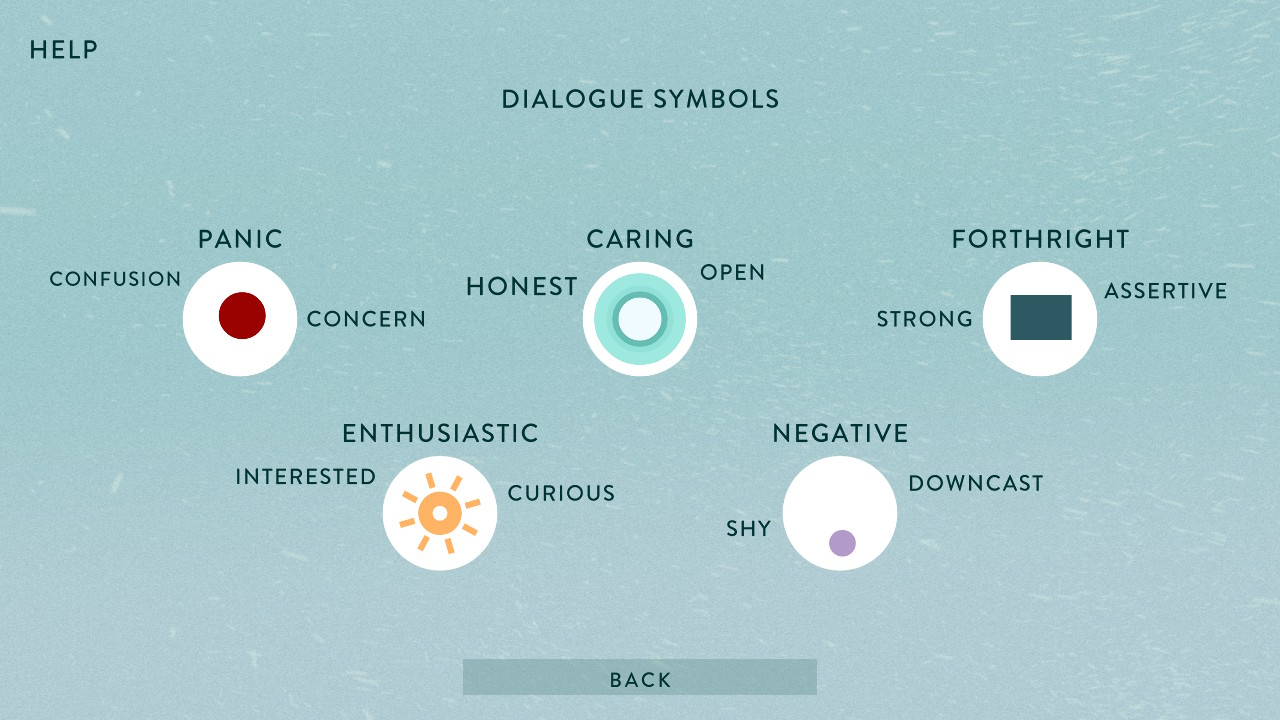

The UI does nothing to detract from this either. In some narrative games, the UI is cluttered or requires some small amount of brain space to process that detracts from the rest of the game, but not here. Prompts appear in large circles, all the better to tap and hold on a mobile device, and each is coded to fit its purpose.

Empty circles highlight interactive objects, conversation prompts are represented by various symbols denoting the tone of the line being selected, and other interactive options are highlighted with easy-to-understand symbols.

Although most prompts are foreshadowed by a small white dot, I did find myself missing their appearance on several occasions, this may be because I was streaming the game at the time, but it is something to bear in mind. I have further thoughts on the accessibility of the game that will be explored below.

I know it’s not a new thing, but it’s a good quality of life feature.

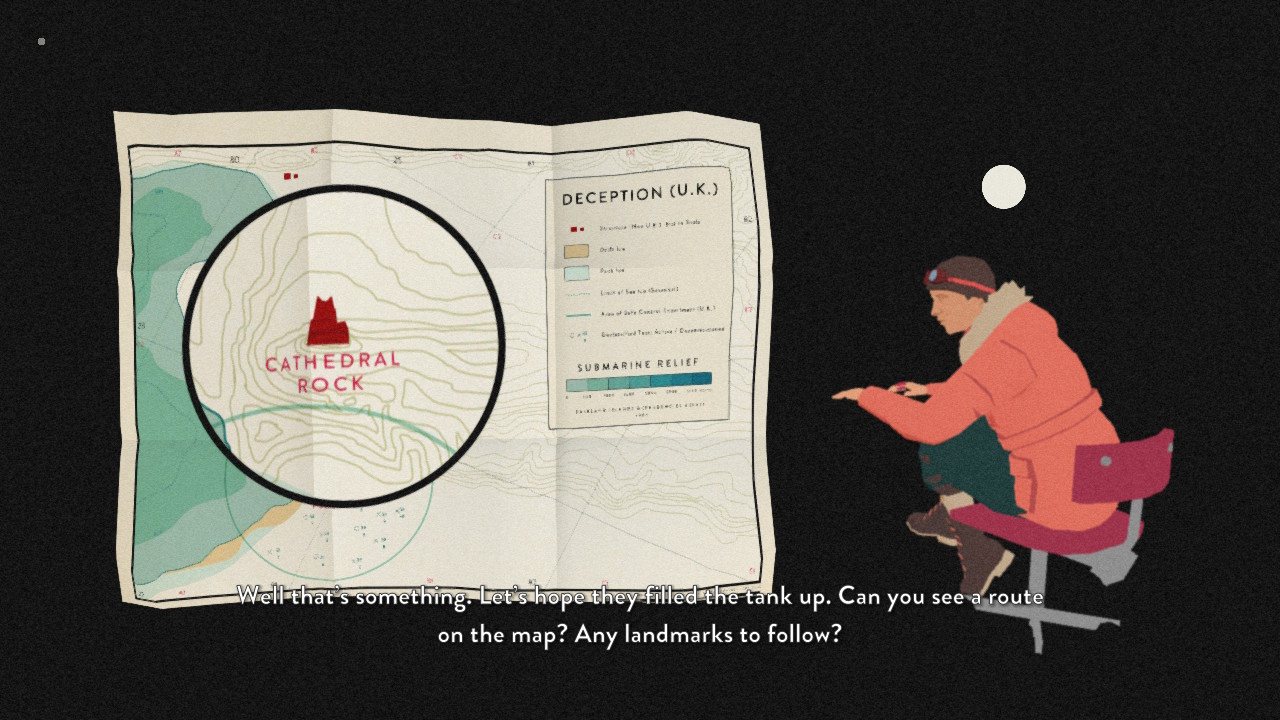

But what of the actual gameplay? As with most narrative games, the gameplay itself isn’t too complex. The game takes place over two time periods: 1964 and an extended period leading up the events of 1964.

In both time periods, most of the gameplay is taken up by wonderfully delivered dialogue punctuated by conversation prompts, chances to explore the environments, or walking sections that take Peter, the protagonist, to the next scene.

Now, I should note that, due to the game being developed for mobile devices, Peter doesn’t move terribly smoothly when using the thumbstick of a controller, and that was something that took some getting used to. Beyond that, however, interactive objects are highlighted from a good distance away, and often provide opportunities for environmental storytelling, and the conversation prompts last for a good length of time before disappearing.

That’s it for gameplay really; at its simplest, this is very much a game of walking from interactive cutscene to interactive cutscene with nothing much in between.

My description of how the movement feels in this game almost as good as the movement itself.

The writing in those cutscenes though? It’s sublime. As I said above, games like SotC are made or broken by their writing and their cast, and the writing does not disappoint. Without wishing to spoil anything, Peter is an academic from Cambridge and the two timelines of the game cover his experiences looking for help in Antarctica, and the events in his life that led him to this point, including meeting Clara, a woman he falls in love with.

Clara is a fellow academic and the two characters allow the writers to explore the ‘old boys club’ feeling of academia from both the outside and the inside, a job which they handled wonderfully. The other members of the cast further build on this, and the global tensions of the Cold War are very much present in both timelines without overshadowing the intensely personal story at the heart of this experience.

As for the story itself, I cannot say much more without spoiling anything, but I will say this: it’s a reflection on how past choices can haunt us, how regret can drive us, and how easy it is to think of the good times when we are struggling.

The ending of the game may not be for everyone, and I will admit that I have mixed feelings on it from a gaming point of view, but it is a perfect capstone of the game’s themes and a culmination of everything that has come before it, as well as a commentary on the nature of choice in real life, not in video games.

As the game progresses, this commentary is hinted at and there are moments of foreshadowing sprinkled throughout that will reward multiple playthroughs.

Credit where it’s due, you can pull this screen up at any time.

A handful of accessibility issues tarnish the experience.

There were two main things that marred my enjoyment of SotC: some minor glitches and the accessibility. To get the former out of the way, characters would occasionally clip through terrain, teleport to ensure they were in position for the next line of dialogue, or otherwise behave in an… unnatural manner due their animation not playing correctly.

Speaking of lines of dialogue, I was surprised at how each flowed naturally into the next, given the timing of the conversation prompts, but there were rare instances when I hit the prompt too early and the start of the next line played over the end of the last. The latter problem was my main issue though.

This isn’t the worst offender but provides a good example of the text crossing multiple background colours.

I mentioned above that the conversation prompts use symbols to denote the tone of the line you are choosing; there are five of these prompts, each with three similar meanings, and it took me a good hour to really get a handle on what each meant.

Even then, I was occasionally surprised by the dialogue choice I had made as the symbols lack necessary context for the actual body of the response. These prompts are also usually timed and, if the timer expires, a default prompt is chosen. Often this is fine, as there may only be one prompt, but I was unwilling to risk my chosen emotional response not being the default option when multiple options are provided.

Perhaps more annoying, however, was the fact that some prompts were so delayed that the time it took to select them, you must hold your selection for a few seconds, resulted in the first prompt to almost time out by the time my selection had finished. If I hadn’t noticed the second prompt in time, I very well might have been forced to use the other prompt by dint of it timing out first.

I hope you can speed read.

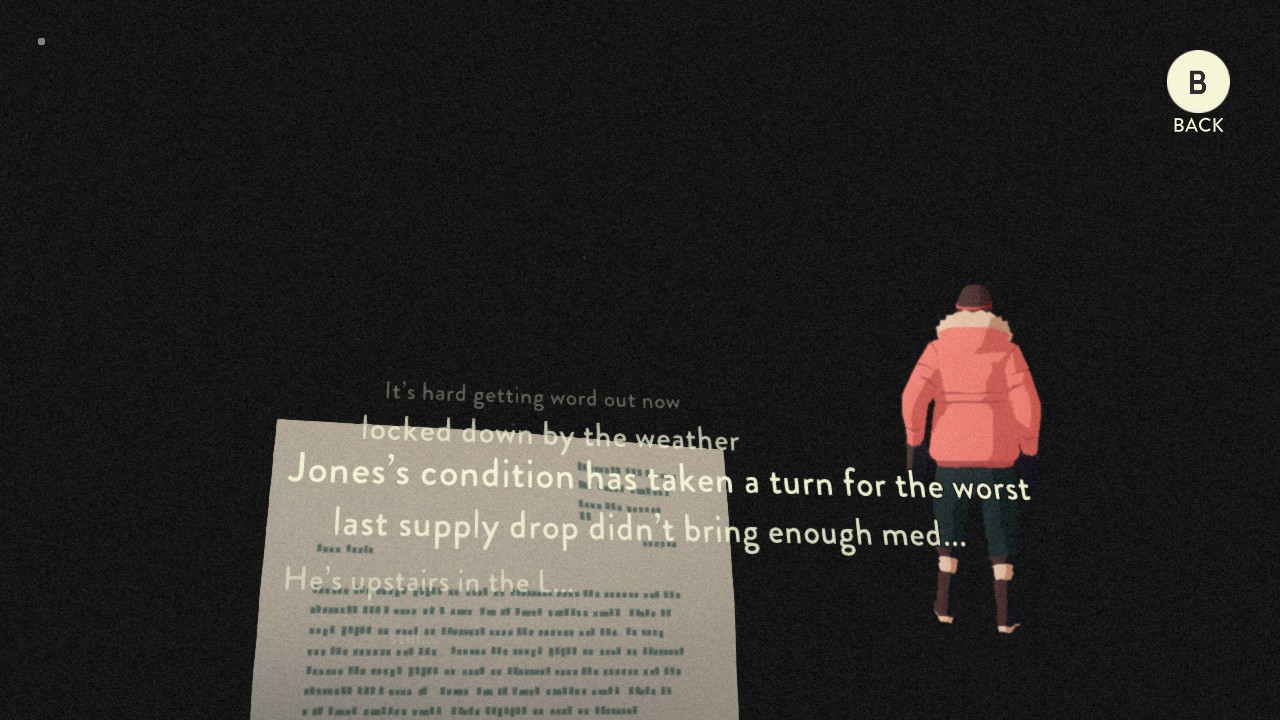

Interacting with environmental objects was similarly challenging in terms of accessibility. Lines of text are spread across a plain black screen and the object itself, they aren’t fully displayed unless they’re in the exact right place on the screen and the scroll sensitivity when using a thumbstick varied based on which item was being examined.

For the vast majority of people, these are likely to be minor niggles but I struggle with Q.T.E.s in other games because of sensory processing issues and several of the conversation prompts really pushed my ability to react to them, and I know several dyslexics who might struggle to read the background information that is used to enhance the game’s story and characters. A mention should be made, however, of the resizable subtitles being clear to read.

They aren’t perfect, but the fact they’re scalable and have a shadow means almost everyone will be able to find a subtitle setting that suits them.

A short game, perfect for a weekend away or a long train journey.

While annoying, I wouldn’t say these issues cropped up enough across the three and a half hours it took me to play SotC to detract from the experience, and even knowing they exist, I am quite likely to replay the game.

The conversation prompts you make throughout the game allow you to tell the game’s story in a wide variety of ways and flavour it to your personal emotional style, but the replayability beyond that is limited to one of two slightly different endings.

SotC seems to be retailing for around £10 and I think that’s a fair price. At the end of the day, games like this are more akin to an interactive audiobook and I would happily pay that much for an experience that has as much of an emotional impact on me as SotC did.

I will be replaying it in the future, when I’m over my current case of the feels and that price point means I can replay it because I want to, not because I feel I have to.

You unlock behind the scenes content as you play, and you don’t even need to find collectibles to do it!

Of course, all of this might not matter if you don’t like narrative games with an emphasis on emotional storytelling and exploring what is means to be human, and to make mistakes.

I wholeheartedly recommend South of the Circle to anyone looking for a short game that will make them connect with its characters on an emotional level whilst also exploring the tension of the Cold War and the sexism rife in academia.

Also, if you play it on the Nintendo Switch like I did, you can use the Switch’s touchscreen instead of the Joy-Cons, and that’s pretty neat. The developers even kept the tiny white square in the top left that was the Pause menu button on mobile devices, although it’s never actually explained anywhere what it is.

If you are interested in my live reactions to the game, my full playthrough can be found on YouTube